Approaching Zero - QFE Operations

This article originally appeared in POPA Magazine - Spring 2024.

Reading time: 5 minutes.

Why do pilots fly Heading up?

……

……

……

Because the world revolves around them.

But it's not just a course you can display relative to yourself. In some parts of the world, your altitude needs to be pilot-centric. Who would have thought flying would include philosophies of relativity?

QNH, QNE, & QFE

These three Q-codes represent different ways we use our pressure-adjustable altimeters. You already use two, even if you are unfamiliar with them. The code is a shorthand carryover from Morse Code, QAA—QNZ, assigned to aeronautical applications. The codes are not acronyms for anything; it was just easier to type three letters than complete questions back in the day.

The list of Q-codes is shrinking because we have advanced radio communication; we tell ATC what we want to do. There are, however, some interesting gems on the list:

QAU - "I'm going to jettison fuel."

QFG - "Am I overhead?"

QAZ - "I'm flying in a storm."

For altimetry purposes:

QNH is the altimeter setting to indicate our height above sea level - what you are used to. QNE is the standard pressure altitude, 29.92 inHG/ 1013 hPa. In the US, we switch to 29.92 at FL180; around the world, the tower can assign the transition flight level. QFE is the altimeter setting that indicates our height above the end of the runway. When you land, it indicates zero.

ICAO is not a fan of QFE. Can you see the conflict? If you should use QFE but mistakenly use QNH, trouble is ahead. For instance, a typical minimum would be 200 AGL for an ILS. A proper QFE procedure would show 200 ft on your altimeter at the MAP. Most airports, however, are above sea level - and if you arrive 200 ft above sea level at that MAP (using QNH by mistake), you may find cumulus granite before you find the airport.

Fortunately, QFE operations are on the way out. They are a holdover of the Soviet Union's way of doing things. It wasn't long ago that flying into Moscow required QFE ops. But they are not all gone yet - there are a few remaining pockets of QFE procedures around Russia and Stans countries.

LGMK - UTDD

For illustration, let's take a flight from the Greek island Mikonos to Dushanbe, Tajikistan. I know you are probably not flying there, but that is irrelevant - this is for science.

The ATIS at LGMK reports two important altimetry details, "QNH 1018 and Transition Level 070." After changing our altimeter setting from inches to hectopascal, we set it to 1018 hPa (30.06 inches) to indicate our altitude above sea level and check that it matches our airport elevation - 405 ft.

On departure, climbing above 6000ft MSL, we transition to QNE ops by setting 1013 hPa (29.92 in). We now are assigned and fly flight levels from FL070 up to our cruising altitude of FL410 and back down to FL100 - which is our transition altitude at the destination airport on the descent.

Now comes the fun. Dushanbe approach says,

"Expect ILS X Rwnway 09, Cleared direct Oktyabrskiy, descend 1800 meters, QFE 694."

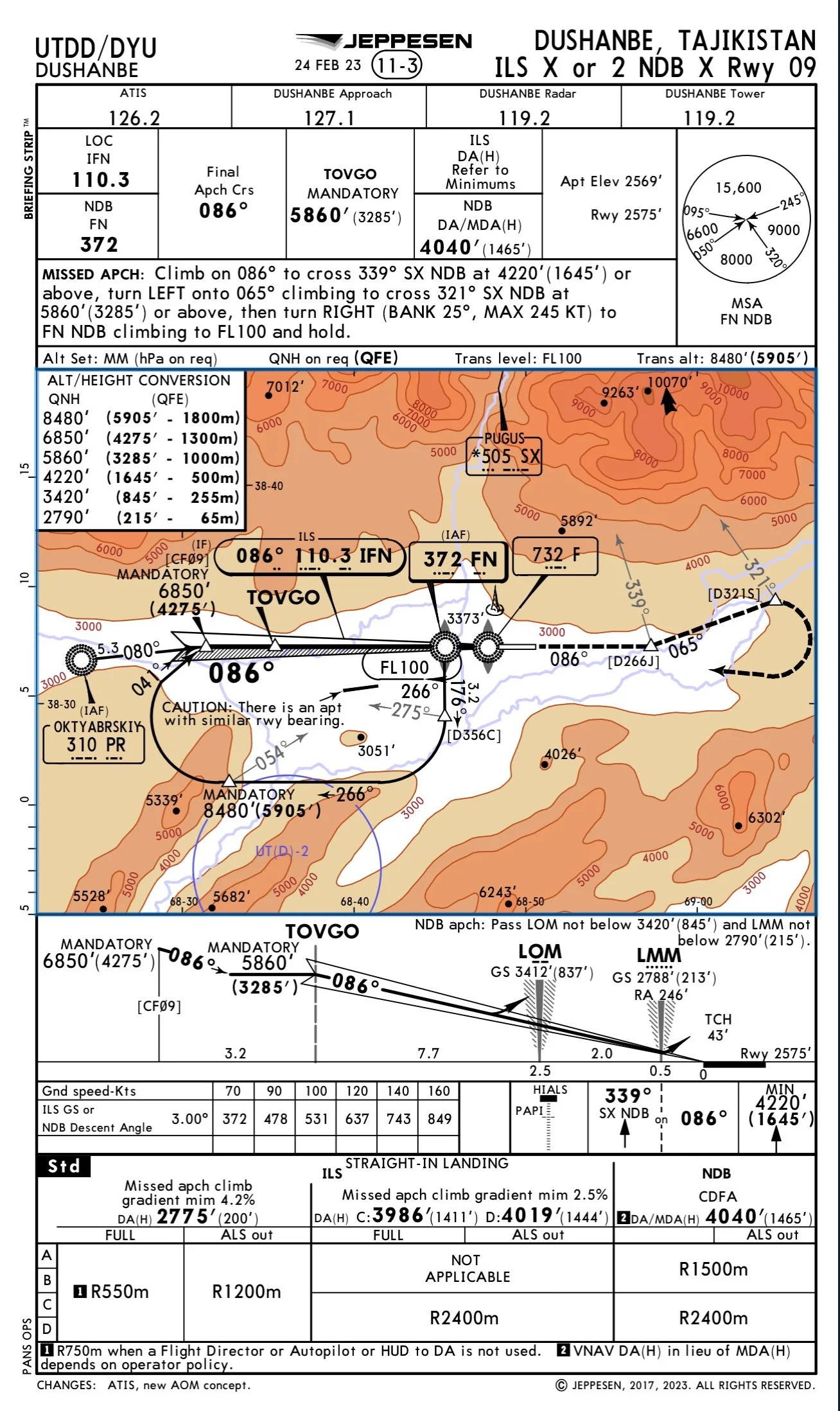

Looking at the chart, it is time to pay attention to the section under the Missed Approach instructions in the header, which is often ignored in the US because it always stays the same.

The Alt Set is now in mm, not hPa. QFE ops are in effect. Trans level FL100. Trans alt 5905 ft QFE. Also, notice that QNH and hPa are available on request.

You have two options: Request the QNH/hPa (which works here but may not be available at all QFE airports) or fully commit to the local QFE and mm operations. When in Tajikistan, do as the Tajiks do.

As we descend through FL100, we change our altimeter setting to mm, set our QFE to 694, and descend to level off at 1800 meters. If your avionics cannot switch to meters, you must utilize the altitude conversion chart conveniently shown on the approach plate. Even if you can convert to mm, your standby instrument may not, so this chart is essential for everyone.

The right QFE column shows what ATC will assign (and also what a Tajikistan government plate would show if we weren't looking at a Jepp chart). The left QFE column converts meters to feet - it is important to switch between the two QFE altitudes fluently. Lastly, the far left QNH column shows the charted altitudes if QNH procedures are used.

We are now cleared for the approach over the PR NDB and begin to descend to cross the two following mandatory altitudes. We need to be at our QFE altitude: 1300m or 4275ft by CF09. Note this is the altitude in parentheses on both the profile and map view of the chart. We then descend to cross TOVGO at 1000m/ 3285ft QFE. When we reach our altitudes, it would be prudent to verify the QNH altitude on our standby instrument corresponds to our primary flight display QFE altitudes by referencing the conversion chart.

Glideslope is alive, and we follow it down to the DA of 65m/ 200ft QFE (also AGL) and see our 2775ft (QNH) on the standby. At touchdown, our primary altimeter reads zero. The pilot is zero feet from their destination, and the world has realigned to meet the expectation that counting begins wherever the pilot sets their wheels.

QFE operations do work. The problem is it is unfamiliar, and if you get it wrong, it can run you into the ground. Notice the elevations on either side of the approach course on the chart - this would be a dangerous airport to mistake QNH and QFE!

Completing QFE operations requires a thorough understanding and a well-communicated brief by crewmembers. It is best to stick with QNH or fully commit to QFE. Have both pilot displays show the same information, triple-check altitudes, be sure of ATC instructions, and, if possible, have a third set of eyes in the cockpit.

One day, QFE operations will be a relic and a future bragging rite for those who got a chance to do them. Even if you're not going to the Stans, consider trying one out at your next simulator training event and become a connoisseur of foreign aviation operations.

Navigate

Article 22 of 22 on your international operations journey. Eject at any time to land at international articles.